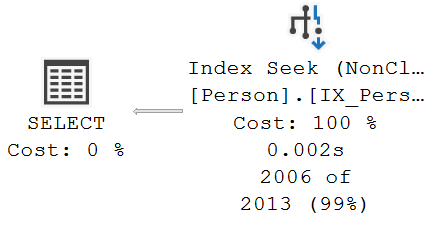

You may have heard of the term “sargable”. SARG stands for Search ARGument, and it refers to a predicate where an index seek can be used by the optimizer. My rule for making a predicate SARGable is that a column must be by itself on one side of the comparison operator. Using the AdventureWorks2016 database, the predicate in this query is SARGable (the query’s execution plan and IO follow):

SELECT P.LastName, P.FirstName FROM Person.Person AS P WHERE P.LastName LIKE 'R%' OPTION (RECOMPILE);

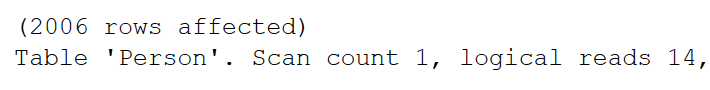

and the predicate in this query is not SARGable:

SELECT P.LastName, P.Title FROM Person.Person AS P WHERE P.LEFT(LastName, 1) = 'R' OPTION (RECOMPILE);

By having the LastName column as a parameter of a function (LEFT) instead of by itself on one side of the comparison operator, the optimizer can’t seek the index that is on that column and has to resort to a table scan. That also results in reading 3819 pages to satisfy the query instead of 14 in the SARGable version.

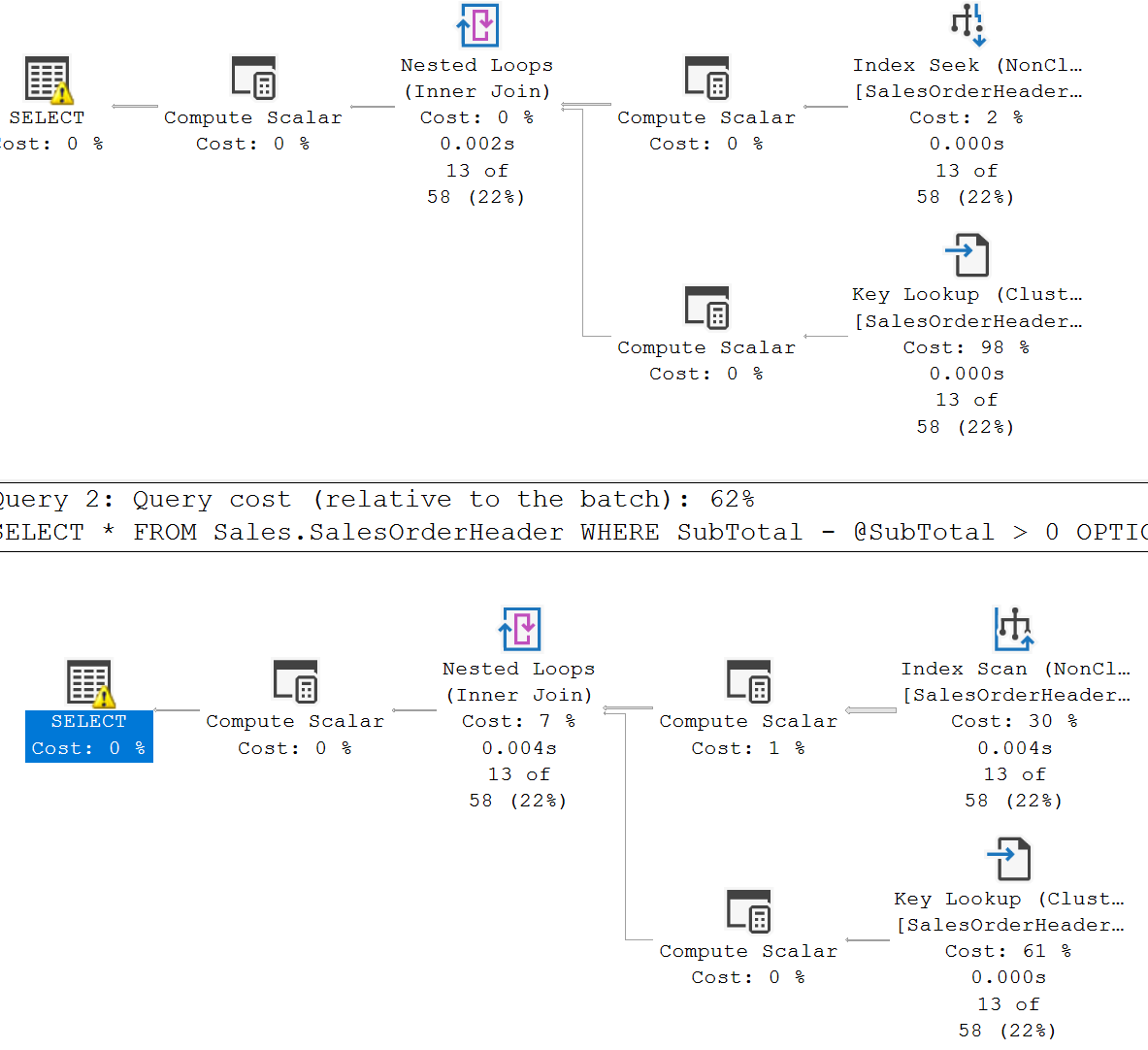

In the following example, I started by adding a nonclustered index on Sales.SalesOrderHeader.SubTotal (I’ll leave that to you). The two queries are logically equivalent, but for demonstration purposes I moved the variable in the second query on the same side of the comparison operator as the column, making the predicate non-SARGable.

DECLARE @SubTotal MONEY = 120000; SELECT * FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader AS H WHERE H.SubTotal > @SubTotal OPTION (RECOMPILE); SELECT * FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader AS H WHERE H.SubTotal - @SubTotal > 0 OPTION (RECOMPILE);

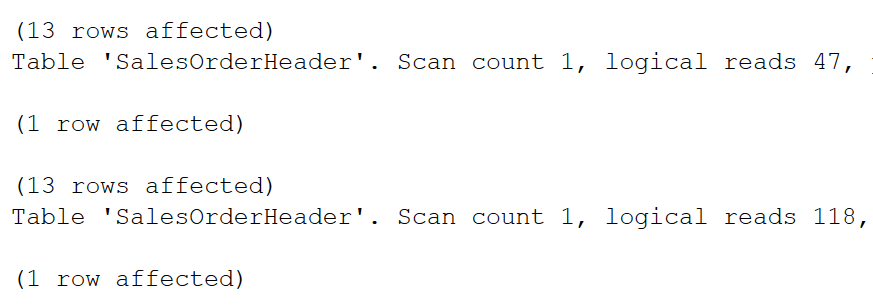

Here are the IO statistics followed by the two execution plans:

The SARGable query read 47 pages of data and did an index seek, compared to 118 pages read and an index scan for the non-SARGable version.

So simple: Always put your column by itself on one side of the comparison operator in the predicate. You won’t always see improvements like these, but occasionally you’ll be a hero.